By: Clifford Eberhardt, Ed.D

Abstract

This paper examines related trends in higher education (grade inflation and graduation rates) and while these trends may appear mutually exclusive, I find causality in this paper. In composing the paper, I examined longitudinal data on grade inflation; reviewed papers written on grade inflation and graduation rates; examined opinions of experts, and examined graduation rates of a selected number of colleges and universities in this country. I my conclusion, not only did I find that grade inflation causes low graduation rates, but ineffective assessment could be the elephant in the room when it comes to these troubling trends.

Other Articles of Interest

- Post- 2019 Top Fraud Case and College Admissions Scandal

- Post- Labor, school athletics and fraud

- Post- Fraud in education and college sports

- Post- Every $1 tax grant leads to 35 cent tuition increase

- Post- State fraud of education funds

- Post- Student loans and executive bonuses

All professions’ frequently look for trends that give an indication of, past, present, and future patterns in occupational development that are essential for professional growth. In medicine, doctors look for trends in patients’ care, pharmacological research, insurance coverage and anything else to improve patient health care. Lawyers look for trends in court precedents, litigation, legislation and clients satisfaction. Businessmen look for trends in marketing, investments, labor cost, global competition and any other trend that affects the bottom-line. Trends are general movements in the course of time of a statistically detectable change. …Usually, a statistical curve reflecting such a change over time helps us identify trends.

Charts and Media you might find interesting

- Media Graph- Coach salaries and average salary Comparison

- Media Graph- College Staffing Changes

- Post- Grade inflation and fraud

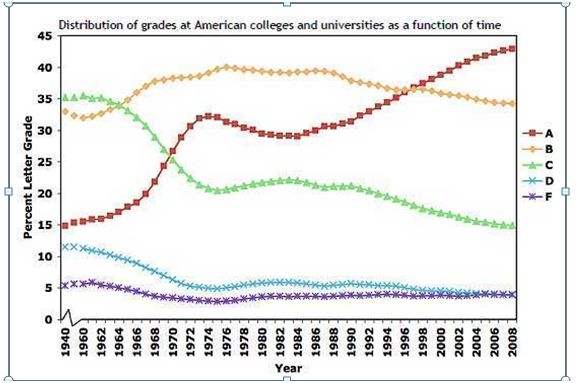

- Media Graph- Grade Inflation

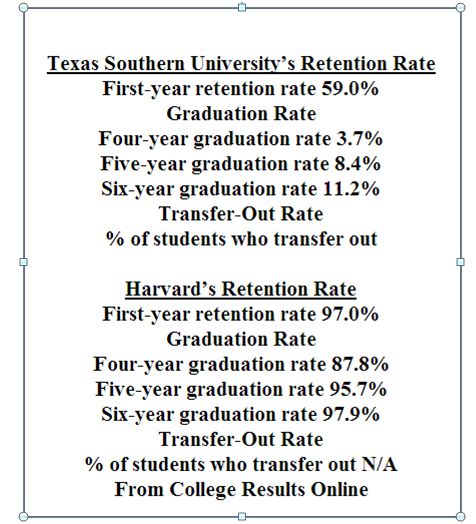

- Media Graph- Retention Rate Comparison

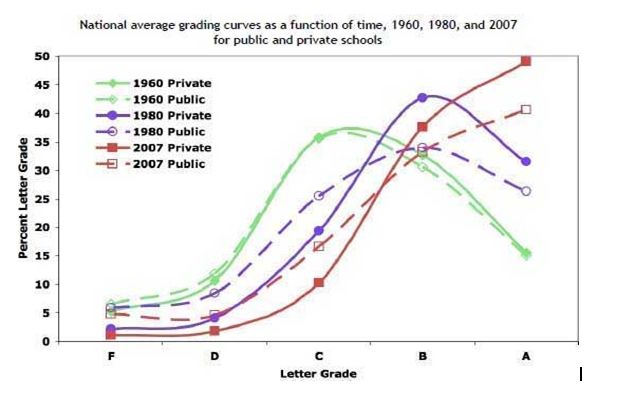

- Media Graph- Average Grade Curves 1960-2007

- Media Graph- Black Campus Change from 1996- 2016

- Media Graph- Grade Distribution from 1940- 2008

In education I look for trends all the time. I look for trends in student behavior, assessment, student retention, student achievement, public accountability and a host of other indices that allow us to provide positive student learning outcomes. In higher education we look for trends to help maximize education — trends which should lead us towards innovation and creative solution in teaching and learning. However, there are two trends that are overlooked in our pedagogical pursuit which are glaring in that if more attention is not forthcoming we could never begin to attack what appears to be incompetence among educational professionals.

Over the past twenty-years, grade inflation and graduation rates are two trends that have called my attention to what we are not doing right in higher education. Grade inflation in undergraduate and graduate programs is our dirty little secret that when brought to light will show how ineffective colleges and universities are when it comes to educating Americans in higher education.

I guess you can trace grade inflation back to the first teachers who had problems ranging from their inability to properly assess the students’ learning outcome to the teachers who give inflated grades for good evaluations. While there are be a myriad of reasons for grade inflation over the eons, nevertheless, it undermines our effectiveness as educators, and our integrity as teachers. According to resent studies on grade inflation, it has increased exponentially of the years.

In the graphic below, I have reviewed historical data collected on letter grades awarded by more than 200 four-year colleges and universities to better understand grade inflation and identify some related causes. The analysis (published in the Teachers College Record) confirm what I’ve been saying all alone in this article, the share of A grades awarded has skyrocketed over the years. Take a look at the red line in the chart below, which refers to the share of grades given that are A’s.

Catherine Rampell has and interesting view on grade inflation. However, one limitation in her article (A History of College Grade Inflation in the New York Times) is that she leaves out an analysis of on-line grading for for-profit colleges and universities like Phoenix and Kaplan. Recently, most for-profit schools were criticized by the Department of Education for incompetence. The industry was on the defensive after a series of federal investigations portrayed it as rife with abuse. They found that recruiters would lure students — often members of minorities, veterans, the homeless and low-income people — with promises of quick degrees and post-graduation jobs but often leave them poorly prepared and burdened with staggering federal loans. (Lichtblau)

But, Rampell’s information on grade inflation for public verse private when exploring this issue was enlightening for me. She states about the graphic above that, “As you can see, public and private school grading curves started out as relatively similar, and gradually pulled further apart. Both types of institutions made their curves easier over time, but private schools made their grades much easier,

“By the end of the last decade, A’s and B’s represented 73 percent of all grades awarded at public schools, and 86 percent of all grades awarded at private schools, according to the database compiled by Mr. Rojstaczer and Mr. Healy. (Mr. Rojstaczer is a former Duke geophysics professor, and Mr. Healy is a computer science professor at Furman University. (Rampell)

Evidence of grade inflation at Ivy League schools was shocking but not so unexpected when I was perusing an article from 2002, in USA Today about grade inflation in those schools. A report found that eight out of every 10 Harvard students graduate with honors and nearly half receive A’s in their courses. This news prompted plenty of discussion and more than a few jokes about grade inflation. But is grade inflation worth worrying about?

No one can argue that really smart students probably deserve really high grades. But, tough graders could alienate the bond between professor and students. Plus, tough grading makes a student less likely to get into graduate school, which could make schools like Harvard look bad in college rankings. These are some reasons cited by professors in explaining why grade inflation is nothing to worry about.

However, in 1966, 22% of Harvard undergraduate students earned A’s. By 1996, that figure rose to 46%. That same year, 82% of Harvard seniors graduated with honors. In 1973, 31% of all grades at Princeton were A’s. By 1997, that rose to 43%. In 1997, only 12% of all grades given at Princeton were below the B range. (USA Today)

With grade inflation so common in America’s colleges and universities, it’s reasonable to assume that the graduation rates would be high. Kind of a common sense initiative for me; the higher the grades, the more graduates. It just followers from common sense and would be counterintuitive to think otherwise.

Not so! While grade inflation is on the rise, ironically, graduation rates among most colleges and universities in America are in decline.

I read a report from the American Enterprise Institute AEI titled, Diplomas and Dropouts: Which Colleges Actually Graduate Their Students (and Which Don’t), by Frederick M. Hess, AEI’s which questioned the low graduation rates of most 2 and 4-year colleges in this country. In the fall of 2001, nearly 1.2 million freshmen began college at a four-year institution of higher, many with expectations and confidence in graduation in four-years. However, that confidence was misplaced. At a time when college degrees are valuable — with employers paying a premium for college graduates — fewer than 60 percent of new students graduated from four-year colleges within six years. At many institutions, graduation rates are far worse. (Steinberg)

In reviewing data from selected colleges and universities on College Results Online, an online web site that gives graduation rates for students who graduate in four-years, five-years and six-years, I found on average most universities rate was around 50%, with a low at most HBCU schools like Texas Southern University to a high from Ivy League universities like Harvard.

The graduation rates about come from College Results Online; a web site that list the retention rates, four-year graduation, five-year graduation and six-year graduation. Comparing Harvard with Texas Southern University the differences are compelling. For first-year retention rate Texas Southern University is 59.0% and Harvard is 97.0%. For Texas Southern University, the graduation rates for four-year, five-year and six-year, the rates are 3.7%, 8.4%, 11.2% respectively. For Harvard, it’s 87.8% for four-years, 95.7% for five-years and 97.9 for six-years. While these are two extremes, most universities’ graduation rates fall between these two extremes.

These two trends (grade inflation and graduation rates) may have countervailing influence on each other in that students who received inflated grades, as a result, are not able to complete terminal projects like capstones. For example, with grade inflation a student can theoretically pass all his/her classes with As, but fail a terminal project like a master’s thesis or capstone. Inflating grades has the potential to handicap students from prerequisite skills they need to complete a terminal project.

Since it is possible for grade inflation to be at the root of both trends, what are some of the reasons given for grade inflation? Richard C. Schiming, on the Minnesota State University, Mankato web site in Grade Inflation Article identifies a number of reasons for grade inflation, from institutional pressure to retain students to higher grades used to obtain better student evaluations of teaching , but assessment was not on his list. Assessment is at the heart of education: Teachers and parents use test scores to gauge a student’s academic strengths and weaknesses, communities rely on these scores to judge the quality of their educational system, and state and federal lawmakers use these same metrics to determine whether public schools are up to scratch.

Designing student learning objectives and effectively assessing learning outcome is at the core of creating lessons and activities that work in the classroom. For most college educators, it was assumed that merely matriculating students through program curriculum ensured that students had mastered the subject. However, this view has recently been challenged because of accountability from students, parents, educators, and accrediting agencies. Stakeholders in particular, and the public in general now require evidence of successful learning. As a result, universities have asked their faculty members to identify the essential aspects of the curriculum that each student should achieve and effectively assess them to avoid grade inflation.

For example, a student in a MA education program may be expected to demonstrate their ability to analyze and synthesize educational data as one part of a set of learning goals. Then, for each learning objective, the department will indicate a method to assess if the student has achieved this goal. One type of assessment measure might be a test on content covered during lectures or a “capstone” project that draws on the entire curriculum in the major.

Moreover, my teaching style is student-centered with five personal overriding learning objectives I have for my students: 1. Student should be able to effectively communicate through speaking and writing, 2. Students should able to work collaboratively with others, 3. Students should be able to effectively use computer technology and the Internet to create lessons and activities, 4. Students should be able to use statistics to analyze educational data, 5. Students should be able to analyze and synthesize educational data for critical thinking. Usually, these goals are align with the learning objectives for the different lessons and activities in a particular syllabus or lesson plan.

Finally, grade inflation and graduation rates are two problems that are manageable, and a work in progress. There must be more research on the relationship between grade inflation and graduation rates, and rigid assessment models must be put in place to assure we have effectively measured our educational outcomes.

Reference

1. Center for Instructional Innovation and Assessment

http://pandora.cii.wwu.edu/cii/resources/outcomes/how_assessment_works.asp

2. College Results Online

http://www.collegeresults.org/default.aspx

3. Lichtblau Eric, Published by New York Times: “With Lobbying Blitz, For-Profit Colleges Diluted New Rules” December 9, 2011

4. Rampell Catherine New York Times Economix, “A History of College Grade Inflation” July 14, 2011, 10:00 AM

5. Schiming Richard C., Grade Inflation Article Minnesota State University, Mankato

http://www.mnsu.edu/cetl/teachingresources/articles/gradeinflation.html

6. Steinberg Jacques, Published by New York Times: Comparing Colleges’ Graduation Rates, June 10, 2009, 12:22 pm

http://thechoice.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/06/10/rates/

7. USA Today, Ivy League grade inflation Posted 02/07/2002 – 10:48 PM ET

http://www.usatoday.com/news/comment/2002/02/08/edtwof2.htm

Other Sources:

American Academy of Arts & Sciences

American Enterprise Institute

Dr. Eberhardt has taught at Central Michigan University for 13-years. His research interest is the study of Cognitive Physiology; which is the integration of computer and human information-processing system(s) to better understand their connection with teaching and learning. His interest in assessment has found that grade inflation is a result of ineffective assessment of learning outcomes. He has edited several online publications, and has published articles on educational technology. He has worked in numerous pedagogical settings that dealt with infusing technology into classroom instruction.